The Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) was first developed by Milton Bennett in 1986. It has been reviewed and revised several times and continues to be relevant to understand the ‘intercultural competence journey’.

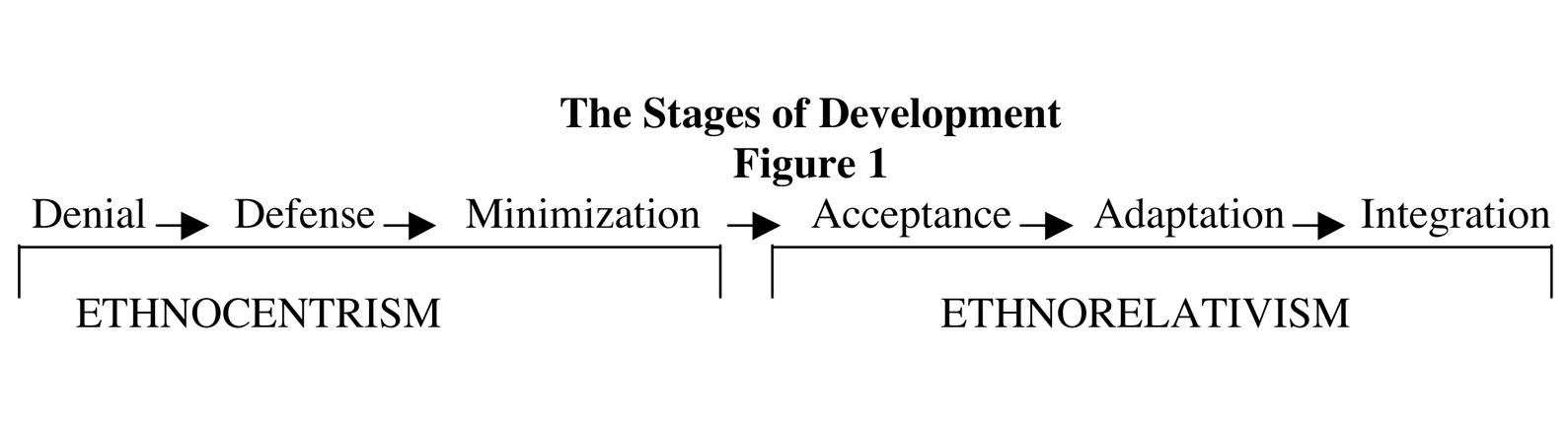

The following developmental continuum presents six ways in which people experience, interpret, evaluate, and interact across cultural differences. It allows reflection and a deeper understanding on how to negotiate differences across cultures.

Stages of Development

Adapted from: www.idrinstitute.org

In the chart above, the three stages on to the left of the center line represent ethnocentrism, the three to the right represent ethnorelativism.

What does it mean to have an ethnocentric view?

- Your own culture is seen as central to reality.

- Beliefs and behaviors that are learned during the process of socialization aren’t questioned.

- Right and wrong are determined by your own culture.

- Cultural differences aren’t noticed or are avoided (depending on which stage you are at).

What does it mean to have an ethnorelativistic view?

- The experience of your own culture is seen as only one way (of many) to organize reality.

- Beliefs and behaviors of your own culture are seen in relation to other cultures.

- Things are viewed as different rather than right or wrong.

- Cultural differences are accepted, adapted to, or integrated into your identity (depending on which stage you are at).

The Stages of Ethnocentrism

Denial

A person at the denial stage does not recognize cultural differences, or sees difference as irrelevant. At this stage a person will disregard statements about the meaningfulness of another culture. If there is some acknowledgement of difference, ‘others’ will be grouped together into categories that homogenize them: “Asians”, “Latinos”, “immigrants”, “refugees”, or “foreigners”.

These categories reinforce stereotypes for a cross-section of people and help the person in denial to degrade or dehumanize others, by attaching labels that view others as having flaws in character, cognitive and physical ability, work, and study ethics, and so on. Others are seen as less complex or not as advanced. A person at the denial stage may not have bad intentions, but their naivety can create negative impacts and consequences.

Defense

A person at the defense stage sees as other cultures as being in competition with their own. Beliefs and statements are polarized, and cultural differences are seen in terms of us-against-them. Defense can manifest when a person or group elevates their own culture over the culture of others. Some current and recent past examples include the Ku Klux Klan in the US, apartheid in South Africa, and ultra-right political parties in several countries. A person at the denial stage may feel victimized when they are called out for creating stereotypes, or making racist or sexist statements, or when they feel that certain ‘equal opportunity’ policies work against them (e.g., affirmative action).

Minimization

A person at the minimization stage sees difference, albeit at a superficial level. There is an assumption that a person’s cultural worldview is shared by others, and that values are interpreted the same way across all cultures.

Although cultural differences may be seen, they can be overlooked or glossed over to maintain a harmonious appearance or to avoid uncomfortable discussions. Sometimes cultural differences are also expressed in terms of human sameness, which allows a person to avoid recognizing their cultural biases, or learning about other cultures at a deeper level.

The Stages of Ethnorelativism

Acceptance

A person at the acceptance stage recognizes that different beliefs and values are shaped by culture, and that different behaviors exist among cultures. They also recognize that other cultures have legitimate perspectives that should be respected. Acceptance does not require that one prefer or agree with behaviors or values of other cultures. It means that a person recognizes and accepts that different worldviews exist (including their own), and that those worldviews guide and determine human values, beliefs, and behaviors.

A person at the acceptance stage may also manifest a greater curiosity about or interest in other cultures and may start to seek out social relationships with those of other cultures.

Adaptation

A person at the adaptation stage is able to adopt the perspectives of another culture. At this stage a person can empathize with others, and can interact in flexible and appropriate ways with people from different cultures.

Within the adaptation stage, a person will be able to discuss their cultural experiences and perspectives in ways that are sensitive to the other culture. A person at this stage extends their beliefs and behavior, knowing that their primary cultural identity is intact, and as such, comfortable and able to operate effectively in a different cultural context.

Integration

A person at the integration stage has a sense of self which has evolved to incorporate the values, beliefs, perspectives, and behaviors of another culture. A person’s experience has been expanded in such a way that they can move between cultures because they are able to take on different cultural worldviews, and express behaviors that are best suited for the context they are in. A person at this stage can shift somewhat effortlessly between worldviews.

Examples of people who have moved into the integration stage include long-term expatriates (who interact with host community members), children born and raised between two cultures, and those from non-dominant groups living in dominant-group settings.

On one hand, integration may be regarded as the ‘ultimate’ stage of intercultural development because it allows a person to move in an out of worldviews, to see things from multiple perspectives, and to understand different value systems. It can, however, create issues because the integrated person lives between two (or more) cultural systems, yet never really feels fully a part of either one – this is known as ‘cultural marginality’.

Example: Cecilia was born in Hong Kong and moved to Australia at an early age. Her parents took her back to Hong Kong for long stays so she could speak Cantonese, learn cultural traditions, and maintain the value systems of her family.

While studying at university in Sydney, she decided to do an exchange program in Hong Kong for a year. With her foot in two worlds, she thought this would offer academic and career opportunities. While on her exchange, she could shift into Cantonese without a problem, and tried to fit in as a Hong Kong student, but she didn’t have a full sense of belonging. To add to this, the local students and professors saw her as an Australian exchange student.

When she returned to Sydney, she had a similar sense to what she felt in Hong Kong. On her first day back at her home university, she was asked by a professor where she was from. She felt stuck between two cultural identities.