Celebrities

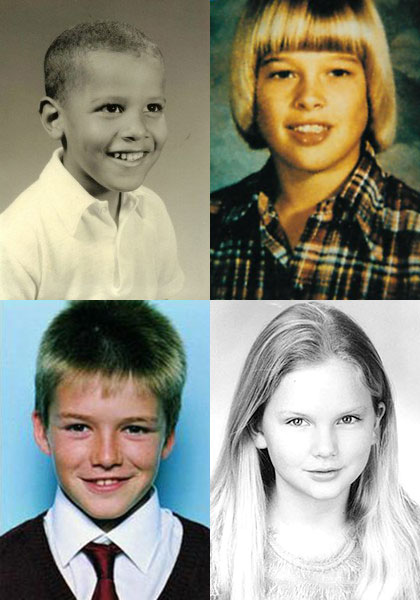

Four famous people in their childhood.

Part One: Discussion

Work with a partner or group and discuss the following questions:

- Can you identify the four famous people from the childhood photos above?

- How would you rate yourself at recognizing and remembering people's faces?

- How would a person's life be affected if they were unable to recognize or remember faces, even those of family members? Consider day-to-day implications, as well as the long-term impact on career and relationships.

Part Two: Active Reading

Exercise

You are going to read a text from an academic journal. Before you read, survey the text and look at the different section headings. After you have surveyed the article, open the exercise to continue.

Defining Prosopagnosia

Developmental prosopagnosia (DP) is a very rare condition in which patients are not able to recognize familiar people on the basis of face information alone. In contrast to acquired prosopagnosia, in which the face recognition deficit evolves as a consequence of head trauma or stroke, DP manifests itself without any overt cause. There are no traumatic incidents in the medical history of affected patients. A definition of DP proposed by Jones and Tranel entails the following criteria: the face recognition deficit is lifelong, it manifests itself in early childhood and it cannot be attributed to acquired brain damage. Other authors, however, include cases with documented developmental brain disease. The first description of developmental prosopagnosia stems from H.R. McConachie; she described AB, a 12-year-old girl who was referred to psychosocial services because of social and psychological problems and was found to be severely impaired in face recognition. AB’s mother also reported not to be able to recognise familiar faces, which was, however, not formally tested. McConachie concluded, “... no hard evidence of neurological lesion was obtained, but the possibility of familial transmission was indicated”.

The Challenges of Living with DP

Prosopagnosia

People with this condition may not recognize themselves in a mirror.

Patients suffering from prosopagnosia have great difficulties recognizing other people. Failure to recognize close friends and family members is reported frequently and some prosopagnosic patients are even unable to recognize their own image in a mirror. Patients are usually able to make use of non-facial cues when attempting to identify a person; often speech or gait is used to recognize others, and patients benefit greatly from the context in which people are met. Semantic knowledge about people is preserved, which suggests that prosopagnosia is not due to general memory problems. In most cases, object recognition is well preserved and even if deficits in object recognition occur, they are much less pronounced than face processing impairments. In everyday life, prosopagnosia has severe effects on social interaction. For example, prosopagnosic people often find themselves in embarrassing situations when they fail to recognize familiar people at chance meetings. They tend to have fewer friends than other people and often withdraw from others. The problem often leads to feelings of guilt, especially in patients who are unaware of an organic cause of their deficit.

The Development of Face Recognition

Normal face recognition undergoes rapid changes throughout the first year of life. Newborns can distinguish the face of their own mother from other faces within the first days of life, at least under certain circumstances. During the first weeks of life, face recognition abilities are somewhat unstable, depending on the assessment technique or the behavioural state of the newborn. At the age of two months, there is activation in the fusiform gyrus when infants look at faces, although many other brain areas are also activated by faces that do not light up in adult brain imaging studies on face recognition. Infants between 3 and 7 months show a stabilized performance which is less task dependent than in younger infants. They are able to identify the gender of faces. Between the 4th and the 9th month of age, a left visual field advantage evolves.

Findings of very early face preference have been taken as evidence for an innate face recognition system. Other authors have emphasised the role of experience for the development of face recognition. Due to extensive training with faces throughout the whole of life, humans become experts in face recognition and brain structures that mediate this skill are the same as those that mediate expert recognition of other visual stimuli. It has been suggested that a strong social interest ensures that most people develop expertise in face recognition and that this social interest is mediated by the amygdala. This account seems to largely ignore the early performance with faces exhibited by infants who did not have the opportunity to accumulate a large amount of visual expertise.

Other recent models incorporate two processes that are thought to be necessary for the development of a functional face recognition system. They argue for an early process that “biases the newborn to orient to faces” and therefore guarantees input to a second experience-based face recognition system that “begins to influence behaviour at 6 to 8 weeks”. The early process is functional from birth and therefore has to be hard wired.

The Cause of Developmental Prosopagnosia

Causes

There is more than one potential cause of developmental prosopagnosia.

According to the two-process theory of development of face processing, developmental prosopagnosia without documented brain damage appears as a result of one of two possible causes: first, a dysfunctional mechanism responsible for passing input to areas of the brain responsible for processing visual information or, second, dysfunction of the area of the brain normally specialising in face processing. On the basis of the available evidence, no decision between these two alternatives seems possible. However, the observation that people suffering from developmental prosopagnosia are able to establish visual expertise in domains other than face recognition provides strong arguments for the absence of an early face orienting system, given that face recognition makes use of the same neural mechanism that mediates expertise for all visual stimuli. There are however arguments that could lead to the assumption that the ability to acquire visual expertise per se depends on visual experience within a critical time period in the same way as the ability to acquire speech depends on being exposed to speech within a certain time window.

The Importance of Studying DP

Developmental Prosopagnosia is a remarkable disorder because it appears in the absence of any obvious brain lesion. It has been suggested that a genetic factor rather than an undiscovered acquired brain lesion is responsible for the condition. DP thus offers the opportunity to study face recognition deficits that are present from birth where face recognition abilities have never evolved.

In recent years, the number of reported cases of developmental prosopagnosia has increased. While there are at least 9 well documented cases published over a period of 26 years, there are considerable differences among these studies with respect to research techniques and the nature of assessed functions. Because DP is so extraordinarily rare, single case studies appear to be the only strategy to gain further insight into this condition. Moreover, evidence from different studies is often contradictory and inconsistent. Suggestions for future assessment of people suffering from DP would be useful to arrive at a better comparability between single case reports.

The Possibility of Treatment

Though the current DP treatment studies demonstrate that face processing improvements are possible with training, it still remains to be seen whether DPs can truly achieve normal face recognition abilities. Even in cases where treatments were effective at improving face processing, DPs' abilities either continued to be below average or the skills learned did not generalize to all aspects of face processing. Furthermore, even after successful training, evidence suggests that skills may not be “self-perpetuating” and it is likely that without continued intervention, DPs return to their dysfunctional ways of perceiving and remembering faces. Thus, though the current demonstrations lay the groundwork for the treatment of DP, there is much work ahead to create effective long-lasting treatments.

Adapted from

Thomas Kress and Irene Daum, “Developmental Prosopagnosia: A Review,” Behavioural Neurology, vol. 14, no. 3-4, pp. 109-121, 2003.

doi:10.1155/2003/520476. Retrieved from http://www.hindawi.com/journals/bn/2003/520476/cta/

DeGutis, J. M., Chiu, C., Grosso, M. E., & Cohan, S. (2014). Face processing improvements in prosopagnosia: successes and failures over

the last 50 years. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 561. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2014.00561. Retrieved from